My brother passed away a month ago, but every midnight I hear strange men’s voices coming from my sister-in-law’s room.

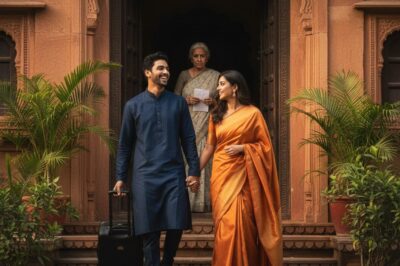

My brother, Arjun, passed away exactly one month ago. I went to my sister-in-law Priya’s house one afternoon in Chennai, as the first rains of the season began to fall. The small alley was flooded with muddy rainwater, the scent of incense from the houses mingling with the characteristic damp smell of petrichor oil. On the small altar, Arjun’s picture sat between two oil lamps, the yellow chrysanthemum petals slightly wilted. They say that during the first month, the spirit of the deceased still lingers, hearing every sound in the house.

Priya opened the door; she looked noticeably thinner, her long hair hastily tied back with a rubber band. Her eyes were the eyes of someone trying to come back to life: reserved, exhausted, but not wanting to disturb anyone. “Stay here so there’s more human presence,” she said, her voice as soft as placing a kullad on the table. I nodded.

For dinner, we ate a simple meal: pumpkin daal soup, a few pieces of braised fish with crispy edges. She ate a few spoonfuls, then set the plate down and said, “You sleep in the living room. Don’t be afraid of the sound of the monsoon wind tonight.” I looked out onto the porch; the raindrops were like threads. I wasn’t afraid of the wind; I was afraid of the silence after the funeral—a silence that… had a sound.

Exactly at midnight, that sound rang out. Not the wind, nor the TV from the neighbor’s house. It was a man’s voice, deep, clear, as if someone were standing in her room whispering: “Darwaza band rakhna, thand lag jayegi.” I jumped up in surprise. Her door was slightly ajar, the faint light like a breath. I was about to knock, then stopped. Maybe she turned on the radio to help her sleep, I reassured myself. When Arjun was alive, he used to listen to late-night cricket commentary on the radio.

The next morning, I asked indirectly, “Last night… did you turn on the radio?” She shook her head, scooping poha onto a plate, her eyes fixed on the food. “No, dear. It’s probably just the wind.”

The second night, the sound of a man’s voice again. This time clearer, slower: “Paani pi le, pyaas lagi hogi.” I heard the sound of the glass being placed on the saucer, the stirring of the spoon. My heart pounded like someone knocking on a ghati. I stepped out onto the porch, standing by the door. In the room, the table lamp cast a pale blue light. I gritted my teeth and returned to bed.

The third night, the voice seemed closer: “Priya, thodi der aaram kar le.” I jumped. That was how Arjun usually called his wife—short, warm, with a hint of teasing. I told her the next morning, stammering: “I… I think there’s something wrong with my hearing, I heard a voice… that sounded like Arjun.” She smiled vaguely, pouring masala chai: “He… he’s gone, dear. Any voice sounds alike.”

I wanted to believe her. But from Wednesday night onwards, at the same time every night, that voice would speak again. Sometimes it would say, “Deewar ke saavdhaan, phisal mat jana.” Other times it would be, “Itna kaam mat karo, aaram karo.” And sometimes it would be, “Maa ne phone kiya hai, kal milne aana.” I lay there listening, cold sweat running down my back. The same voice, the same tone. Not the radio. Not the drunkard from the alley. It was a man’s voice right in my sister’s room.

On Thursday, the owner of the grocery store at the end of the alley shook her head and sighed when she saw me going to the market in my sister’s place: “Priya is acting strangely lately, still talking to someone at night.” The words fell like a rope into a deep well. I ignored them, quickened my pace, but my heart was heavy.

On Friday, I walked past the drying yard and saw a freshly washed men’s kurta on the line, its hem fluttering. I froze. It was exactly the same style Arjun usually wore… but it was… brand new, the paper tag still attached. I didn’t dare ask.

That evening, she brought me a bowl of hot sambar, saying, “Eat some more. You’ve gotten so thin.” I mumbled. I looked at the dark circles under her eyes, the veins bulging on the backs of her hands. People often do strange things when they’re too tired. I clung to that reason like a handrail in the rain.

On Saturday night, I couldn’t take it anymore. When a man’s voice clearly rang out: “Priya, teesre almarah mein ek towel hai…” (Priya, there’s a towel in the third drawer…), I stormed into the room.

The door swung open, the desk lamp casting a cold blue light. Priya sat on a wooden chair, a small microphone in front of her, a laptop open, the screen displaying blue sound waves like a torrential rain. A small speaker sat next to Arjun’s portrait. On the altar, the incense ashes had burned out.

The man’s voice came again from the speaker: “Darwaza band rakhna, thand lag jayegi.” That voice was Arjun’s—unmistakable: the slow, deliberate ending, the subtle resonance of the word “band.”

I stood frozen, as if struck in the chest. She looked up, strangely calm: “You’re in at the right time,” she said, “I’m doing a test run.”

“Test… what?” I stammered.

She tilted the screen toward me. On it was a strange software program, with pre-typed text alongside the sound waveforms. A folder with the note: “Arjun — Voicemails.”

“Arjun’s voice,” she said slowly, as if afraid of breaking the name, “is being run by a computer. I’m ‘training’ it.”

I didn’t understand. “Running… his voice? By what… machine?”

She rubbed her temples: “It’s artificial intelligence (AI). The IIT university students helped me. They sampled his voice from voicemails he sent to his mother, to clients, and old recordings on his phone.” “If something is missing, just put it together; if the rhythm is off, fix it. The night is quiet, and machine learning is easier.”

I gripped the edge of the table. “What… what are you doing with it?”

She looked up at the altar, then down at the picture frame, her voice low: “Mom’s been confused at night lately, calling Arjun’s name but not remembering. The doctor said we should have a familiar sound in the house to help her feel less anxious. Arjun’s voice is gone, that rhythm of life is broken. I want… to reconnect it. At night, this machine will remind Mom to ‘drink water,’ ‘go to sleep,’ like before. I’m afraid to tell you—afraid you’ll be scared.”

I slumped into a chair. I asked about the kurta hanging outside.

She smiled softly: “I bought a new one for Mom. She kept hugging Arjun’s old kurta and crying, saying the fabric was too worn out. I bought one similar, so she can hug it to ease her longing—so her scent will soak into the new fabric, to ease her heartache.”

I sighed. In life, there are things that reason hasn’t had time to understand before emotions silently take action.

Before I could say anything, the screen flickered, another signal appeared, and a man’s voice spoke again, but it wasn’t the message my sister had typed. It was softer, more hurried:

“Rohan, if you hear this, I… I’m probably gone. Don’t blame Priya. Don’t let outsiders name our family’s pain.”

I jumped to my feet. “Rohan”—my name. I looked at my sister. Her face was pale. “This… wasn’t from the machine,” she said quickly. “It’s a voicemail saved on his old phone. The night he died, he left three messages for you that he didn’t have time to send. I… just found them. I didn’t dare let you hear them… I was afraid you wouldn’t be able to bear it.”

I leaned against the cabinet. So, during the nights I tossed and turned, my sister sat here with the machine and the voices, piecing together the rhythm of our family life. The fake voice to keep Grandma asleep. The real voice to keep me from breaking down.

“And… the men’s voices I heard the nights before,” she continued, “some nights it was a machine, some nights it was… real people. The group of students connected me to the overnight helpline—people who have lost loved ones, calling when they can’t sleep. Arjun used to volunteer, working from midnight to two in the morning. I… am now in his place.”

I was astonished: “You… listened to strangers?”

“Just listening,” she said. “I don’t know their names. I listen so I don’t think negatively. I listen to know that my family’s pain isn’t alone. I didn’t say anything because I was afraid the neighbors would gossip. Here, there are voices every night; people give them names and believe what they think.”

Everything suddenly became clear. I was ashamed for having doubted. I was grateful for having doubted—so now, I understand.

“Let me…,” I took a deep breath, “listen to all three text messages.”

She nodded. We turned off the ceiling lights, leaving only the table lamp on. Arjun’s voice rang out, both hurried and trying to sound calm:

“Rohan, if you’re late today, don’t let Priya eat alone. I’ll go eat with her. Don’t let her sit there listening to the sound of spoons and chopsticks alone.”

“If Mom gets confused tomorrow, don’t try too hard to correct her. Remind her by offering her hand to hold; she’ll remember from the warmth, not from words.”

“There will come a time when you will become the pillar of our family in my place. Don’t let outsiders name the pain of our family, okay?”

I cried—sobbing, tears falling onto the tiled floor. My sister didn’t comfort me, only remained silent. His voice faded, leaving only the sound of rain outside.

The next morning, we brought the loudspeaker to Mom’s house. She sat by the window, her eyes vacant, her hands fumbling in the air. My sister turned on the loudspeaker: “Maa, paani pi lo” (Mom, drink some water). She looked up, her eyes wide open. Her trembling hand paused, then reached for the glass of water. She took a sip, her lips quivering. Then she wept, silently. In that moment, I saw her ten years ago: cheerful, chattering, calling out “Arjun beta” to ask her to open the spice jar.

That afternoon, I sat on the charpai (bamboo bed) on the porch with my sister. The scent of mogra (jasmine) wafted from the neighbor’s house. My sister took a small, half-knitted, moss-green woolen hat from the basket under the table and placed it in my hand.

“It’s from Arjun,” she said, watching the shadows of the two of us on the patio. “He bought the yarn before Diwali. He told me to learn to knit it for… our child.”

I looked up sharply. My sister bit her lip, a smile both familiar and strange, like when she first came to live with us as a daughter-in-law: shy and gentle.

“I’m pregnant,” she said. “Six weeks.”

The wind blew in from the alley, making the corrugated iron roof rattle. I clutched my wool hat. Everything suddenly took on a different meaning. Those nights she sat alone, not just to teach the voice-learning machine his voice, not just to listen to strangers, but so the baby in her womb could hear its father’s voice—whether it was a fake voice, whether it was a real voice faded with time.

“I’m sorry,” I said, my voice choked. “I thought… something bad.”

“Everyone in this neighborhood thinks that, Rohan,” she replied softly. “But everyone will reach out when their family truly needs them. We live between those two things. I just hope to put the right name back on what’s really happening.”

That night, at midnight, there was another man’s voice in her room. I didn’t jump up like before. I stood up and knocked softly. She opened the door and invited me in. A small speaker was placed near her belly. Arhun’s voice—smoother now—was reading a short story from the Panchatantra, stumbling over a few difficult words, pausing to catch his breath, then continuing. I sat opposite him, listening silently, like a child learning to read.

At the end, a voice—whether machine-generated or a new recording—was unclear:

“Priya, apna khayal rakhna. Rohan, ghar sambhal lena. Baccha, hawa se mat dar.”

I no longer distinguished. I didn’t need to. In that small room, there was enough human warmth—of him, her, mother, me, and an unborn child whose name was already in our hearts: Aasha.

The funeral last month had taken away the warmth of the house. A month later, we relit the light—with a machine-learned voice, a listening line through the night, a half-knitted woolen hat, and truth called by its proper name.

The unexpected ending came to me one afternoon. My mother slept peacefully in her hammock, her hat covering her forehead. Priya lay on her side, her hand clutching her stomach, the small speaker silent. I sat on the porch, opened my laptop, and registered a new account on the overnight helpline. My shift was from midnight to two in the morning. I filled in the “Reason” section: “Kyuki mujhe ek aadmi ki jagah nibhani hai. Aaj raat se, main wahin khada hoon.”

That night, at midnight, I heard a man’s voice again in Priya’s room. I didn’t barge in. I sat by my phone, wearing my headphones, and spoke to a strange male voice on the other end of the line—perhaps from the next street, perhaps from another city—saying: “Aap apne ghar ke dard ka naam kisi aur mat hone dena.”

At the same time, from Priya’s room, a voice—Arjun’s, the phone’s, or both—came out: “Baccha, hawa se mat dar.”

Our home is now full of warmth. And I understand: the initial fear wasn’t about Priya having another man, but about not knowing how to name the sounds in the night. Once we could name them correctly, the night was no longer frightening. It was just a shift—where we stood together until dawn.

News

The husband left the divorce papers on the table and, with a triumphant smile, dragged his suitcase containing four million pesos toward his mistress’s house… The wife didn’t say a word. But exactly one week later, she made a phone call that shook his world. He came running back… too late./hi

The scraping of the suitcase wheels against the antique tile floor echoed throughout the house, as jarring as Ricardo’s smile…

I’m 65 years old. I got divorced 5 years ago. My ex-husband left me a bank card with 3,000 pesos. I never touched it. Five years later, when I went to withdraw the money… I froze./hi

I am 65 years old. And after 37 years of marriage, I was abandoned by the man with whom I…

Upon entering a mansion to deliver a package, the delivery man froze upon seeing a portrait identical to that of his wife—a terrifying secret is revealed…/hi

Javier never imagined he would one day cross the gate of a mansion like that. The black iron gate was…

Stepmother Abandons Child on the Street—Until a Billionaire Comes and Changes Everything/hi

The dust swirling from the rapid acceleration of the old, rusty car was like a dirty blanket enveloping Mia’s…

Millionaire’s Son Sees His Mother Begging for Food — Secret That Shocks Everyone/hi

The sleek black sedan quietly entered the familiar street in Cavite. The hum of its expensive engine was a faint…

The elderly mother was forced by her three children to be cared for. Eventually, she passed away. When the will was opened, everyone was struck with regret and a sense of shame./hi

In a small town on the outskirts of Jaipur, lived an elderly widow named Mrs. Kamla Devi, whom the neighbors…

End of content

No more pages to load