My mother-in-law was visiting from the countryside. I had planned to get up early and make pho, but as I entered the kitchen, I saw her standing there with a bowl of something. The food she had left for me angered me so much that I put the 20,000 rupees I had given her in the cupboard…

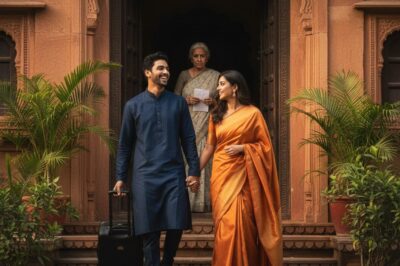

My mother-in-law had arrived in Delhi from the countryside of Uttar Pradesh the previous afternoon. The Uttar Pradesh State Road Transport Corporation bus had been wobbling for four hours; her plastic slippers were dusty, and she carried an old cloth bag: a few bundles of greens, some guavas plucked from the garden, and a bag of poached eggs. She placed the things on the floor and quickly glanced around the living room, kitchen, and balcony, like someone observing the “weather” in a strange land. She said, “The house is beautiful. You must have worked very hard to buy it.” The compliment was like the gentle tap of a spoon on the edge of the bowl—polite yet cold. I smiled and said a few sentences, reminding my husband—Dev—to drag his suitcase into the guest bedroom. Dev eagerly said: “Mom, come and have some fun for a few days. Living in the countryside all the time is boring.”

That night, I—Nisha—tossed and turned. Any daughter-in-law knows that some of Mom’s days at work can be longer than a week. Hearing Mom’s mild cough in the room, I remembered a bowl of chicken yakhni. The moment I saw the packet of desi eggs, I had this idea: I would wake up early tomorrow morning, simmer the yakhni broth with the aroma of cinnamon, star anise, onion, and roasted ginger, shred the chicken, boil the egg noodles, add garlic seasoning—and give my mother a bowl of “chicken yakhni noodle soup” in my own way. I wasn’t adept at most dishes, but this was my “specialty.” A bowl of yakhni could bridge two distant shores: mother and daughter-in-law.

The five o’clock bell rang. I sneaked into the kitchen.

As I entered the door, I saw my mother standing by the gas stove; a bowl of steam billowing from her hand. The smell wasn’t of yakhni, but of Maggi noodles cooked in chicken broth: a yellow, murky liquid, laced with grease. Both mother and the kitchen were awake. She picked up the bowl to take a sip, looked at me, hesitated for a moment, then corrected herself: “Have breakfast, I’ve cooked.”

I looked at the bowl my mother had placed next to me: mine—Maggi too. The noodles were loose, some wilted green onions, a few chopped chicken pieces, the skin yellow and mushy like a ripe banana left in the fridge too long. Where did the chicken come from? The chicken I’d left in the fridge last night so I could cook yakhni in the morning—it must have gone into the pot. There was a crackling sensation in my chest—like a pinch of salt had been overturned. I swallowed and said: “Yeah… I was going to make yakhni for you.”

Mom laughed: “Oh, come on, yakhni and tripe! Let’s quickly eat Maggi. I woke up at four, and everything was ready. That’s how it is in the countryside.” She spoke as if she were putting the final punctuation mark on a long paragraph, without waiting for anyone to edit it.

I pulled up a chair, touched the soft noodles with a spoon. Rustling. Dev came out of the room, his hair still tangled, yawning and stretching: “Oh my God, it smells so good. Mom woke up early?”—”Mom has a habit of sleeping in.” Dev picked up his bowl, ate it with great gusto, and turned to me: “Oh, you’re not eating?”

I nodded. A desi chicken came to mind, its soft white bones after a slow cook, and a bowl of yakhni, wafting with the aroma of roasted ginger, roasted onions, and badiyas. That was my naive dream. The reality was a bowl of Maggi left uneaten, with “Mom’s full” written on it, as if a no-retreat sign had been hung in the middle of the kitchen.

I went into the room, opened the cupboard, and reached for the small box containing the envelope containing the 20,000 rupees I was about to give my mother. I almost pulled it out, then stopped. My finger curled up like a snail curling into its shell. I placed the envelope. A very soft “knock.” Was it something to hide from someone? Perhaps it was just my own trembling.

The next day, my house felt like it was tied with rope. Mom arranged the shelves according to her own rules: heavy at the bottom, light at the top. I was used to placing the bowls in the middle, so now I had to bend over every time I needed a bowl. Mom put the vegetable washing basin in the sink, the sesame candies in the sugar jar, and the coffee jar next to the spice powder. I poured the coffee, and Mom said, “Children, drinking coffee makes you angry.” I choked back, “Yes.” Mom followed me into the nursery, lifted the blanket to see if the baby was kicking it while sleeping, and whispered, “When I gave birth to three children, applying betel leaf and celery stopped the vomiting.” I smiled as if a hanger was hanging from my mouth. Dev went to work and texted: “Come home early this afternoon. I want to eat bottle gourd and chana dal.” I bit my lip. The dal was cooked. But in my heart, every word “I want” was knocking… knocking…

That night, I—Nisha—tossed and turned. Any daughter-in-law knows that some of her mother’s days at work can be longer than a week. Hearing her cough lightly across the room, I remembered a bowl of chicken yakhni. The moment I saw the packet of desi eggs, I had this idea: Tomorrow morning, I’ll wake up early, simmer the yakhni broth with the aroma of cinnamon, star anise, onion, and roasted ginger, shred the chicken, boil the egg noodles, add a garlic tadka—and serve my mother a bowl of “chicken yakhni noodle soup”—my own version. I wasn’t adept at most dishes, but this was my “specialty.” A bowl of yakhni could bridge two distant shores: mother and daughter-in-law.

The five o’clock bell rang. I sneaked into the kitchen.

As I entered the door, I saw my mother standing by the gas stove; She held a bowl that was steaming. The smell wasn’t of yakhni, but of Maggi noodles cooked in chicken broth: a yellow, murky liquid, laced with grease. Both Mom and the kitchen were awake. She picked up the bowl to take a sip, looked at me, hesitated for a moment, then corrected herself: “Have breakfast, I’ve already cooked.”

I looked at the bowl my mom had placed next to me: mine—Maggi too. The noodles were loose, some wilted green onions, some chopped chicken pieces, the skin yellow and mushy like a ripe banana left in the fridge for too long. Where did the chicken come from? The chicken I’d left in the fridge last night so I could make yakhni in the morning—it must have gone into the pot. There was a sharp crack in my chest—like a pinch of salt had been overturned. I swallowed and said: “Yes… I was going to make yakhni for you.”

Mom laughed: “Oh, come on, yakhni and tripe! Let’s quickly eat Maggi. I woke up at four, and everything was ready. That’s how it is in the countryside.” She spoke as if she were putting the final punctuation mark on a long paragraph, without waiting for anyone to edit.

I pulled up a chair, touched the soft noodles with a spoon. Rustling. Dev came out of the room, his hair still tangled, yawning and stretching: “Oh my God, it smells so good. Mom woke up early?”—”Mom has a habit of sleeping in.” Dev picked up his bowl, devoured it with gusto, and turned to me: “Oh, you’re not eating?”

I shook my head. A thought came to mind… a desi chicken, its soft white bones simmering over low heat, and a bowl of yakhni wafting with the aroma of roasted ginger, roasted onions, and badiyas. That was my innocent dream. The reality was a bowl of Maggi left unattended, with “Mom’s full” written on it, as if a no-retreat sign were hanging in the middle of the kitchen.

I went into the room, opened the cupboard, and reached into the small box containing the envelope containing the 20,000 rupees I was going to give my mother. I almost pulled it out, then stopped. My finger curled up like a snail retreating into its shell. I placed the envelope. A very soft “knock.” Wanting to hide from someone? Maybe just to hide my own trembling.

The next day, my house felt like it was tied to a rope. Mother arranged the shelves according to her rule: heavy at the bottom, light at the top. I was used to placing the bowls in the middle; now, whenever I needed a bowl, I had to bend over. Mother placed the vegetable washing basin in the sink, the sesame candies in the sugar jar, and the coffee jar next to the spice powder. I poured coffee, and Mom said, “Children, drinking coffee makes me angry.” I choked back, “Yes.” Mom followed me into the nursery, lifted the blanket to see if the baby was kicking it while sleeping, and whispered, “When I gave birth to three children, applying betel leaf and celery stopped the vomiting.” I smiled as if a hanger was hanging from my mouth. Dev went to work and texted: “Come home early this afternoon. I want to eat bottle gourd and chana dal.” I bit my lip. The dal was cooked. But in my heart, every word “I want” seemed to be knocking… knocking…

At lunch, I accidentally made it salty; Mom frowned: “The food above is too salty.” At dinner, I made less rice because I thought I’d eat less, and my mother put down her chopsticks: “It’s like breakfast at a hotel, not enough to fill your stomach.” This month the electricity bill was high, and my mother said: “Women and girls are so rich now that they don’t know how to save.” I went to my grandparents’ house to wash some clothes for my daughter, and my mother said: “Your grandparents are always easygoing; pampering you too much will spoil you.” These words were like rubbing salt into a wound.

At night, I opened the cupboard, engraved the envelope, and closed it again. “Or should I just give it to you?” a voice whispered. Another voice said: “Why? Because of a bowl of Maggi? Has my sense of power in the kitchen suddenly disappeared?” I tucked the envelope deeper into my sweater.

That night, my daughter had a fever. Her forehead burned like a burning stone, and she was weak. The thermometer read 39.2. I took my daughter, along with the fever reducer, into my arms and wiped her body. My mother pulled out a towel: “Give it to me. Apply the betel leaf—celery is for fever reduction.” I quickly said: “Mom, I’m following the doctor’s orders.” My mother rolled her eyes: “Doctor, doctor! I gave birth to three children, and when I got sick, I took care of myself.” The child screamed. Dev was in the middle, his eyes swirling like postage stamps without envelopes. I quickly said: “I’ll take you to the hospital.” My mother stopped me: “It’s just a little fever, and you’re rushing to the hospital right now! What a waste of money.”

I hugged my child and walked straight away. Dev somehow managed to grab the keys, looked at his mother, and ran after her. Mom stood at the door, her plastic slippers and her shadow longing in the light. I knew she felt left behind.

At the hospital, the doctor examined her, brought down her fever, and put her in an IV. The baby lay still. Dev

At the hospital, the doctor examined her, brought down her fever, and put her in an IV. The baby lay still. Dev held my hand: “I’m sorry. Mom is afraid to spend money, afraid the city will swallow you up.” I looked at him, my fatigue vanishing, a feeling of emptiness filling me. “I’m afraid this is different. I’m afraid our home is someone else’s home.”

We arrived home around dawn. Mom sat at the table, a bowl of cold white porridge in front of her, the spoon stuck to one side. He looked at me, his voice heavy: “I thought… she would be just like her older siblings. Poor thing, she ate whatever she could find, and covered herself with leaves when she had a fever.” I laid the baby in the crib and covered her with a blanket. Turning, I said softly: “Everything is different here, Mom. Tell me whatever I say. But I am responsible for my actions.”

Mom bowed her head and nodded. The silver hairs on the edges of her ears moved gently like thin blades of grass.

The next morning, I decided to make yakhni. Dev took Mom to the market. I stayed home to wash the bones, boil noodles, fry ginger and onion, and roast the vadis. I wanted the yakhni to be like a new map, with lines and boundaries. When they returned, Mom, holding a desi chicken in a net bag, continued to talk: “The chicken seller said this chicken was raised outdoors, very strong, and cleanly.” Dev smiled: “You chose correctly.”

I said: “Mom, let me make it. I’ll treat you to a bowl of yakhni today.” Mom paused and looked at me for a moment. She put down the bag, looked at the stove, at the pot of clean water, the scent of cinnamon, almonds, and ginger mingling. She said softly, like a breath: “Yes… it’s up to you.”

In the afternoon, the three of us sat at the table. I poured the water, added the meat, sprinkled onions, and seasoned it with garlic. Mom picked up the bowl and tasted it. She closed her eyes, as if listening to some strange song, some notes of which were very familiar. “Delicious,” Mom said. Then she said: “When I was little, I used to sell tea and poha outside the bus station. Every morning at 4 a.m., I would break out in a sweat watching the water boil. When street vendors were banned, I quit. Do you know what I hate most? I hate when a customer sits down and says, ‘Make me a good cup of tea.’ As if I’d made myself a bad cup of tea.” She laughed, occasionally. “Maybe that’s why I… was in a hurry that morning. When I saw the chicken, I immediately thought of eating it quickly. Maggi is from a poor family, so once it’s cooked, consider it a meal. I had forgotten that things are different here, and so am I.”

“Maggi is from a poor family” rang out to me like a nail coming out of an old plank. The crack wasn’t a window, it was just air coming in. “I had forgotten who you are too,” I said. “I thought the food would speak for itself. But sometimes I have to say it out loud: Mom, this is my kitchen. I want to make yakhni for you. I hope you’ll respect that.”

Mom nodded: “I’m listening.” She put down her chopsticks, her gaze fixed on her rough hands with bitten nails. “In the countryside, old people like me feel precious about what they can do. Up here, everything is in abundance, and I feel useless. I hold a spoon, but I can’t figure out where to get it. So I scramble to cook, to see if I still have anything left.” She looked up and said, “But I also understand that I’m encroaching. I apologize for that bowl of Maggi.”

That afternoon, I went out to dry clothes, and the wind blew open the door of my mother’s closet. I reached out to close it, and suddenly, I saw my mother’s cloth bag. It was so old, its edges frayed, sewn with green and red thread. Inside the bag was a small notebook, its cover cut from a noodle shell. I opened it curiously. It was clearly written: “Transportation fee: 200. Gift amount for grandchildren: 50. Amount for the child: None.” I was shocked. I should have handed over the envelope, but a little angry about the bowl of Maggi made me refuse. My mother had assumed she would give it to me without asking. Next to it were several small packets of salt, MSG, and pepper. It’s a habit of chefs: wherever they go, always have spices ready, as if they were brought from home.

At night, clearing the table, I said: “Mom… I was a little upset yesterday morning. I was going to give you some money for the trip, but kept it. Sorry.” Mom waved her hand: “Oh, money isn’t worth anything. I’m here to visit my grandson, a bowl of yakhni is enough.” She paused for a moment and said: “But… if you’re going to send it, send the corrugated iron roof for my sister. The house is leaking.” I nodded. I suddenly felt relieved. I opened the cupboard, took out the 20,000 rupee envelope, counted it again—it was still there. I placed it in Mom’s hand: “Keep it. Send it when you have time. Dev and I will send more.”

Mom took the envelope, her eyes elsewhere: “Thank you.”

On the last day, it was raining heavily. The sound of the rain from the balcony sounded like someone washing the courtyard. Mom gathered the supplies, arranged the remaining vegetables, took down the guava, and said: “Keep it in a cool place so the stalks don’t rot.” She walked around the kitchen, touching the shelves and the gas stove. I called out, “Mom.” Mom turned. “Next time you come up, we’ll cook yakhni together. Mom roasts ginger, and you do it better than me.” Mom smiled, “I’ve roasted ginger all my life, now I’ll roast it for you, it’s perfect.”

Dev took Mom to the bus station. I stood at the door, holding my son in my arms, watching our backs slowly shrink. Before leaving, Mom slipped me a plastic bag: “Desi eggs, for breakfast tomorrow. But don’t make Maggi,” she said in a slightly teasing voice. Mom and I laughed, a gentle laugh like the rain that had just stopped.

When Mom came home, the house suddenly became quiet—so quiet that I could hear the clock ticking. I wiped the table, washed the dishes, and put away the dishes. I opened the cupboard and looked at the empty space where the envelope had been kept. I placed a piece of paper there: “Our kitchen rules: Whoever cooks—let them decide. Whoever eats—let them give their opinion after eating.” I stuck it on the kitchen wall. Not to remind Mom, but to remind Dev and me: no one “finishes” a meal for someone else’s life. We have to talk to each other before the water boils.

The phone rang. It was Mom’s name: “We’re home. In the car, I was sitting next to the bean vendor; she said your yakhni was delicious, and the way you served it and sprinkled onions showed you loved it.” I smiled: “Who told you?”—“I told you.” She paused: “My older sister’s roof is leaking badly. When the rain stops, I’ll call someone to cover it. Don’t send me any more; I’ll take care of it.” I said: “Mom, just mind your own business. The kitchen here has its own rules. There’s a roof over there. Everywhere there’s something you need to take care of.”

A month later, Mom called: “It’s harvest season here. The rice smells wonderful. If you two are free, come and play.” Dev checked the calendar—the weekend was free. I nodded: “Come.” Mom could hear my smile through the waves, her voice full of joy: “I caught chicken. Yakhni or Maggi?” She giggled. I replied: “Yakhni, Mom. But let me add spices to it. And Mom… roast ginger.”

In Mom’s kitchen, the honeycomb-like coal stove was glowing red. I sat on a low chair, a pot of broth simmering. Mom stood next to me, turning ginger over the embers, its skin charring, fragrant. We were silent, as if listening to the sound of waves rising underground. Dev held his baby in the courtyard, the neighbor’s children running around. Mom turned and asked the same question: “Do you know what I hate most about tea customers?” I smiled: “Yes, I hate people who say, ‘Give me a nice cup of tea.’” She nodded: “Yes.” Then she said: “But what I love most is the person who invites me to cook with them. Like today.”

The yakhni was served. I added it, my mother sprinkled onions on it. Dev took a photo and said: “Post this as ‘Yakhni from my mother’s house.’” I stared: “My father’s house.” My mother laughed: “Every house is a home.”

We ate. The broth was sweet, the chicken was chewy, and the green onions were green. I thought, turns out, a clear ending for family isn’t one that divides victory and defeat, one that’s not decided by anyone. A clear ending is a day when the kitchen has rules, words have their place, the elders have work, the young have power, and every bowl of yakhni is cooked with both memories and the present.

This afternoon, I woke up early again. I poured water into a pot, added ginger and onions. I texted my mother: “Mom, come tomorrow. I’ll make yakhni. Fry the ginger.” The message came back: “Yes. And don’t hold back. Whatever you give is light.” I stood in the kitchen, smiling. This time, the pot boiled right on time. No one said, “Mom, it’s done.” No one was pushed out. We learned to stand together—in the aroma of chicken yakhni.

News

The husband left the divorce papers on the table and, with a triumphant smile, dragged his suitcase containing four million pesos toward his mistress’s house… The wife didn’t say a word. But exactly one week later, she made a phone call that shook his world. He came running back… too late./hi

The scraping of the suitcase wheels against the antique tile floor echoed throughout the house, as jarring as Ricardo’s smile…

I’m 65 years old. I got divorced 5 years ago. My ex-husband left me a bank card with 3,000 pesos. I never touched it. Five years later, when I went to withdraw the money… I froze./hi

I am 65 years old. And after 37 years of marriage, I was abandoned by the man with whom I…

Upon entering a mansion to deliver a package, the delivery man froze upon seeing a portrait identical to that of his wife—a terrifying secret is revealed…/hi

Javier never imagined he would one day cross the gate of a mansion like that. The black iron gate was…

Stepmother Abandons Child on the Street—Until a Billionaire Comes and Changes Everything/hi

The dust swirling from the rapid acceleration of the old, rusty car was like a dirty blanket enveloping Mia’s…

Millionaire’s Son Sees His Mother Begging for Food — Secret That Shocks Everyone/hi

The sleek black sedan quietly entered the familiar street in Cavite. The hum of its expensive engine was a faint…

The elderly mother was forced by her three children to be cared for. Eventually, she passed away. When the will was opened, everyone was struck with regret and a sense of shame./hi

In a small town on the outskirts of Jaipur, lived an elderly widow named Mrs. Kamla Devi, whom the neighbors…

End of content

No more pages to load