On the wedding day, the poor bride was looked down upon by her husband’s family. In the middle of the party, her mother-in-law sarcastically said, “What does your family have besides empty hands?”

On the morning of the wedding, the rain stopped at the right time, as if someone had pulled up a damp curtain. The restaurant courtyard was still wet, the smell of new lime and jasmine flowers mixed together. I sat in front of the mirror, the makeup artist said, “Priya has such beautiful skin, no need to cover up.” I laughed, joking, “It’s because I wash my hands a lot.” She didn’t understand, because my hands were indeed… white. Literally white: the knuckles were dark from washing with alcohol a lot, the palms were thin and taut, and the latex gloves had stuck together in tiny patches. People call “empty hands” to mean poverty; but for me, “empty hands” is something I have trained myself to touch other people’s skin without trembling.

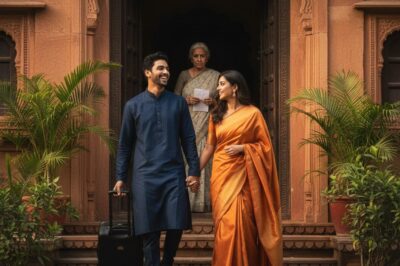

My husband’s family arrived on time. To say “on time” means fifteen minutes ahead of schedule. Gorgeous saris, neat sherwanis, passing eyes, lingering on my rented wedding lehenga for a moment longer before moving on. I stood beside Arjun—my fiancé—at the entrance, receiving every handshake and greeting. Arjun’s mother, Shanti, was beautiful in the way a woman has known how to hold her head high all her life. She didn’t look me in the eye, just looked at my hands clasped together in front of my stomach, then looked away, and said a sentence as light as setting a teacup:

“What do you have at home… besides your empty hands?”

The sentence fell to the marble floor, not breaking, but sending small sparks. The cousin standing behind her laughed, saying: “What she meant was that Priya needs to try harder.” A sister-in-law chimed in: “Luckily she also knew how to choose a modest lehenga.” I heard every last syllable drawn out, like a needle thread deliberately misaligned. Arjun squeezed my hand. I whispered: “It’s okay.”

My mother awkwardly stepped forward, thrusting a silk package into Mrs. Shanti’s hand: “A gift from home, mithai gajar ka halwa my daughter made herself.” Mrs. Shanti did not accept it, looked at the maid: “Take it.” Then she turned back to the guests, her voice full of enthusiasm: “The in-laws on the other side are very kind, but unfortunately… they are empty-handed.”

I pulled my hand from Arjun’s and helped my mother to a chair. She said: “Come on, son. We get married to start the morning.” I nodded. Actually, the day is sometimes too bright, making people squint and not see clearly.

The party began. Yellow lights fell on the U-shaped tables, glasses stood like a small army. The MC said familiar lines, children ran after each other, a live band played a lyrical ghazal. I smiled, counting my breaths. My chest was tight in my wedding dress, making me breathe narrowly, in short bursts.

When the two families raised their glasses, Mrs. Shanti stood up and said into the microphone:

“Today is a great day, our groom’s family is happy to have a good daughter-in-law. I just hope… ah, I just hope that the other family will try hard from now on, but your family… has nothing but empty hands, right?”

The whole hall gave a very soft “oh”—closed-mouthed “oh” sound. The old people coughed, the young people chuckled. My mother was confused, her hands clasped together as if praying, her lips trembling. Arjun was about to raise his hand to speak, I touched a finger to his wrist: “Let me.”

I held the microphone, my voice not loud, nor shaking:

“Yes, it’s true that I only have empty hands. But they are for work. I hope that in the future… I will use them to cook roti for my parents, wash my mother’s sari, and serve my father a bowl of porridge.”

Shanti curled her lips, about to say more, when… Mr. Vikram—Arjun’s father—who was sitting next to her, suddenly grabbed his left chest, his face pale as if someone had drained all the color from it. The glass of lassi in his hand fell to the carpet, the sound muffled by the music.

He opened his mouth as if drowning, his breathing gradually becoming intermittent. Cold sweat beaded on his forehead. The collar of his sherwani shook. He reached out, as if to grab the edge of the table, then slid down.

“Dad!” — Arjun shouted.

The “dad” sounded like a knife tearing through the ornate decoration. People crowded around, sleeves rushing, names being called out in confusion. Someone shouted “call 108!”. Someone else said “loosen your tie!” The waiter trembled, dropping the tray of spoons.

I put down the microphone, walked quickly, almost running. I knelt beside Mr. Vikram, my right hand on my carotid artery, my left hand pulling the chair behind me for ventilation. Rapid, chaotic pulse, low blood pressure. Cold forehead, wet back of shirt. Typical angina. I looked up:

“Arjun, take off dad’s tie! Uncle, open the lobby door, please give me some air!”

“Tell the kitchen to get me two aspirin, if there is nitroglycerin, put one under the tongue.”

“The dispatcher’s sister called 108, said: 62-year-old male, severe left chest pain, sweating, suspected myocardial infarction, hypotension, address…”

“Everyone back off, don’t crowd!”

My voice naturally returned to the habit of commanding on the line: short, clear orders, no insistence. People often listen to such a voice, even when they don’t know who I am.

Mrs. Shanti looked at me in surprise, as if for the first time recognizing a real person’s voice behind the bride’s dupatta.

I handed over the aspirin. I broke the nitro tablet in half, pushed it under his tongue, and held his head slightly elevated. He groaned softly, his hands twitching. I unbuttoned the second button of his shirt to make it easier for him to breathe. His pulse slipped further. I heard running footsteps outside the door, the ambulance siren hadn’t arrived yet but the cold air was already in.

Mr. Vikram blinked, then his eyes… went blank, his pulse slipped to a silence. I put my hand on his sternum, looked at Arjun:

“Stop breathing! Prepare for CPR!”

“Priya…” — Arjun gasped.

“Trust me.”

I stacked my hands, placed them in the right position between my sternum, counted one, two, three… The soft carpet didn’t give enough pressure, I told the waiter to put a board under his back. His chest moved with the rhythm of my hands, pressed five centimeters deep, released all the pressure to let his heart fill. I counted 30 compressions, then blew two times, covered him with a thin cloth, tilted his head at the right angle. The smell of perfume mixed with sweat, lassi lingered in the air. Years of nights spent on duty in the emergency room suddenly came back through my fingers.

“Where’s the AED?” — I asked the restaurant manager — “Do you have a defibrillator?”

Luckily, the restaurant had one. An employee rushed in with a yellow box. I ripped off the tape, stuck the two electrodes in place, and turned on the machine. The woman’s voice was cold: “Heart rate analysis. Charging. Back away from the patient.” I lifted my hand, pushed everyone away, and looked at the screen—ventricular fibrillation. The machine said “Electroshock.” I pressed. His body jolted slightly. I turned around and continued to apply pressure. After about thirty seconds, I felt a pulse return—weak but steady. I looked up at Arjun:

“It’s better. Is the 108 here yet?”

“It’s almost there!”

Vikram opened his eyes, his breathing was ragged. I leaned closer and spoke slowly:

“Uncle, I’m Priya. Listen to me. Try to breathe, I’ll scold you a lot more after this.”

He nodded slightly. A tear fell from the corner of his eye. I took his hand—the hand with the callouses of a man who had carried heavy loads to build the company—and said: “Bite this pill gently, don’t swallow it yet.” He obeyed.

The 108 siren pierced the air. The lobby door swung open. Two ER nurses pushed the stretcher in, followed by the doctor on duty—my colleague—whose eyes froze:

“Doctor Priya?”

It was as if someone had turned on a very bright light in the eyes of the entire hall. The name—my real name in the hospital—was bigger than my wedding lehenga, and there was no need for introduction.

“Please transfer quickly. Anterior myocardial infarction, suspected LAD obstruction, blood pressure rising again.” — I informed, briefly.

“Do you have an IV ready?” — the nurse asked.

“Yes. Peripheral vein, left arm.”

I helped them lift him onto the stretcher. Arjun walked close by, his hands shaking. Shanti suddenly tugged at my shirt:

“You… who are you?”

“My daughter-in-law.” — I looked straight at her. — “And an ER doctor at the city hospital. I work the night shift a lot so I rarely… show my face.”

After saying that, I drove off with the 108 car. The wedding party was left behind, the font “Happiness” swaying in the wind like a misplaced word.

In the cardiac intervention room, everything happened as if it were a practice. I wasn’t on duty that shift, but I stood outside the glass door, coordinating with the team. They placed a stent, opening up the anterior coronary artery. The cardiac enzyme index began to drop. Blood pressure rose again. Mr. Vikram passed through the narrow door between night and day.

When he was transferred to the intensive care unit, Arjun hugged me, saying a very small sentence:

“Thank you.”

“Don’t thank me in the hospital.” — I laughed. — “Thank you when you get out of here. Here, thanking is easy… to pass.”

Mrs. Shanti stood two meters away, unable to walk. She looked at me as if looking at an object that I thought was plastic but turned out to be solid wood. She approached, softly:

“I… am sorry.”

I took off my gloves and washed my hands, the cool green liquid flowing through my fingers, washing away the remnants of a party. I remembered the sentence: “What does your family have besides empty hands?” and suddenly… loved that sentence. Because it contained the frivolity of people when faced with things they don’t know.

“Don’t apologize in the hospital, Mom.” — I turned to her, borrowing the way of speaking that was always economical with words. — “Apologize outside. Here, apologizing is easy… to slip away.”

She smiled awkwardly, her lips trembling. The confident lines on her face suddenly blurred. Night. The hospital was quiet like a city: there was still the sound of gurney wheels rolling, the sound of machines beeping, the deep sound of plastic slippers on the floor. I went into the doctor’s lounge, rested my head on my arms, and dozed off for ten minutes. When I woke up, the phone screen lit up: Mom texted, “Don’t let yourself get cold. Your mom has been watching the wedding live stream for a while now, and seeing you… saving people, she’s shaking.” I chuckled. Mom trembles in everything she does, except when it comes to loving me.

The next morning, the attending physician announced: “It’s okay. Her nerves are fine, her heart muscle is largely preserved.” I exhaled, as if I had placed a chair in the right corner of the house. At noon, the restaurant staff called Arjun: “Yesterday’s party… was a failure, we’ll refund a portion and give you two another dinner.” I said: “Give it to the hospital staff. Everyone was hungry yesterday.”

In the afternoon, we returned to the restaurant to get our things. My husband’s relatives sat silently. No one mentioned gajar ka halwa anymore. No one talked about “empty-handed.” I walked through the lobby, and heard an uncle whisper: “That girl is a doctor, my goodness. But she’s so good at hiding it.” Another person replied: “Hiding something… if we don’t ask, then that’s fine.”

Mrs. Shanti greeted me at the door. She walked slowly, like someone learning to walk on new ground. She said:

“Mom… I’m sorry.”

“Yes,” I replied, shortly.

She thought I was cold. Actually, that “yes” was to accept, to close the lid of a box that I accidentally opened yesterday. She sighed, then suddenly held my hand, her hand was warmer than I thought:

“Mom… stupid. You thought I was poor… empty-handed. Who would have thought…”

“I’m also empty-handed, Mom.” — I shrugged. — “It’s just… these hands have touched many lives. That’s why they’re so white.”

She bowed her head. That was the first time I saw her bow to me without fear of being seen.

We moved the wedding procession “in my mind” to another day, no wine, no music, just went to eat a bowl of pav bhaji under the bridge. Mr. Vikram was discharged from the hospital after two weeks, his back straighter than before, smiling or pursed his lips—as if smiling with his heart that had just been operated on.

The day he came home, we went to burn incense for our ancestors, the altar was filled with smoke, yellow marigold flowers stood in a row, shining brightly. He put his hand on my shoulder:

“Please… take Dad to the follow-up appointment on time. Dad… is scared of the hospital.”

“Yes, but don’t run away this time.” — I winked.

Mrs. Shanti scolded lovingly: “What a strange way to talk.” Then she turned to me, put a silk bag on the table: “Gajar ka halwa, I tried it. It’s sweeter or richer than… your mother’s, I’ll tell you the truth.” She finished speaking, laughing self-deprecatingly. I opened it, the carrot was cut evenly, the sugar was glistening. My mother nodded: “It’s delicious. But it’s not cooked to the right temperature.” Both mothers laughed. The laughter of people who know how to light the right fire.

One evening, Arjun and I went for a walk by the lake. The wind made the neem leaves turn over. Arjun asked:

“Why didn’t you tell Mom earlier that you were a doctor?”

“Why did you tell her earlier?” — I kicked the pebble with the tip of my shoe. — “To be respected for my profession? Or to endure for my profession? I want people to be upset because I am Priya, not because I am a doctor.”

“Are you afraid that people will… take advantage of you?”

“I am afraid that people will be hurt.” — I looked at the water—a wrinkled mirror. —“At the hospital, I once refused a ‘VIP’ who wanted to take my bed. She was… a relative of my father. I didn’t accept because there were so many people waiting. That day, she… cursed. If I say I am a doctor today, my mother will remember the past, my hands will no longer be white. I want to keep something… to touch people without getting stuck.”

Arjun was silent. He squeezed my hand, warming his hands that were used to the cold alcohol of antiseptic.

“Thank you for saving my father. But…” — He looked at me — “what I am most happy about is that last night, you saved… the word ‘empty-handed’.”

I burst out laughing. Yes, there are words that, if not saved in time, will die unjustly.

Our wedding didn’t happen again. But the marriage did, and it started with the mundane: washing dishes, cleaning carpets, reheating the food that night for the hospital security guard. Mrs. Shanti occasionally called me to go to the market: “Doctor, go to the market and cook garam masala for my father.” I teased: “I changed the name of the dish: resurrected pig heart.” She scolded: “What a talkative girl.” But she laughed loudly, her eyes wrinkled, took out her wallet and paid without any hesitation.

One day, she looked at me for a long time and said:

“That day… if you hadn’t been there… I don’t know how to live. I apologize to you once again, even though you told me not to ask in the hospital. This is a market, it probably… won’t go away.”

“It won’t go away.” — I nodded.

She held my hand. Her hand was hot. Mine, still white.

The surprising ending of this story, if outsiders wanted to hear it, would be: “The poor bride who was despised suddenly revealed herself to be a famous doctor.” But for me, the surprise lay elsewhere: empty hands—a term once used to humiliate—turned out to be what I carried to lift a father through a serious illness, to pull a mother out of the pit of arrogance. And also what helped me put the spoon back in the right place after a meal: not too hard to break the porcelain, not too light to slip off the table.

The last night before Mr. Vikram’s re-examination, I sat in the living room, cutting gajar ka halwa with Mrs. Shanti. She held the knife unevenly, the carrot slices sometimes thick, sometimes thin. I reached out to adjust, she gently tapped my hand: “Don’t always help others. Let me cut it myself.” I withdrew my hand, smiling. My mother whispered in my ear: “Now that’s… sasural

I looked at my hands under the yellow light: the faint blue veins, the traces of rubber powder, the small scars from the scalpel. I thought, if someone asked me in the future: “What do you have at home besides your empty hands?”, I would say: “Yes. A heart that knows how to shrink at the right time, so that your hands are big enough to support you.”

Outside, a few small drops of rain fell, as if someone had tasted the water before pouring it all out. I pushed the door open and took a deep breath. The city had just finished washing its face, the faint smell of alcohol, the warm smell of garam masala. Arjun came out of the kitchen and asked: “What time will you go with your father tomorrow?” I replied: “Six thirty. A little early, there’s traffic.”

“Doctor Priya, please go to bed early.” — Arjun said sternly.

“Yes, the patient’s family.” — I joked.

I turned off the light, touched the tabletop, and felt a sticky streak of halwa. Wiped it off with a warm towel. My hands, whiter in the dark, touched everything wanting it to be a little less rough. Somewhere, the siren 108 pierced the night. I held Arjun’s hand. Our hearts, fortunately, beat in unison. And fortunately, no one asked… what else my family had besides a pair of empty hands. Because they had seen: those hands were enough to keep an evening from being broken.

News

The husband left the divorce papers on the table and, with a triumphant smile, dragged his suitcase containing four million pesos toward his mistress’s house… The wife didn’t say a word. But exactly one week later, she made a phone call that shook his world. He came running back… too late./hi

The scraping of the suitcase wheels against the antique tile floor echoed throughout the house, as jarring as Ricardo’s smile…

I’m 65 years old. I got divorced 5 years ago. My ex-husband left me a bank card with 3,000 pesos. I never touched it. Five years later, when I went to withdraw the money… I froze./hi

I am 65 years old. And after 37 years of marriage, I was abandoned by the man with whom I…

Upon entering a mansion to deliver a package, the delivery man froze upon seeing a portrait identical to that of his wife—a terrifying secret is revealed…/hi

Javier never imagined he would one day cross the gate of a mansion like that. The black iron gate was…

Stepmother Abandons Child on the Street—Until a Billionaire Comes and Changes Everything/hi

The dust swirling from the rapid acceleration of the old, rusty car was like a dirty blanket enveloping Mia’s…

Millionaire’s Son Sees His Mother Begging for Food — Secret That Shocks Everyone/hi

The sleek black sedan quietly entered the familiar street in Cavite. The hum of its expensive engine was a faint…

The elderly mother was forced by her three children to be cared for. Eventually, she passed away. When the will was opened, everyone was struck with regret and a sense of shame./hi

In a small town on the outskirts of Jaipur, lived an elderly widow named Mrs. Kamla Devi, whom the neighbors…

End of content

No more pages to load