Convicted of manslaughter, daughter-in-law despised by her husband’s entire family – only her mother-in-law still quietly does this every month

I walked out of the prison gate on a November morning as quiet as an old photograph. Two rows of mango trees stood straight, their leaves rustling together with a paper-thin rustle. The officer who processed my release handed me a bag: a pair of plastic slippers, a gray sweater that had turned gray, a contact book with relatives. Everything was so light that I felt like my arms had forgotten how to hold heavy objects.

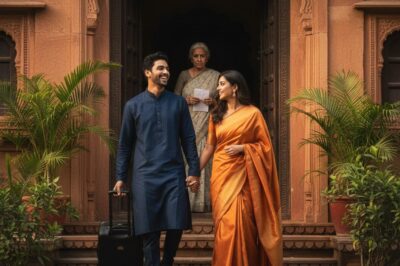

Across the street, Mrs. Meera — my mother-in-law — stood leaning against a low neem tree, holding a faded cloth bag. She wore an old black sari, one end of the cloth covering her neatly tied gray hair. She picked up the bag and walked toward me, her leather slippers rustling on the ground. “Go burn incense for him,” she said in a low voice. “We’ll figure it out.”

Those were the first words she said to me three years, eight months, and eleven days after the court sentenced me to twelve years in prison for “involuntary manslaughter” — my husband, Raj.

My husband’s extended family had despised me like an oily rag. The dinner on the day of my sentence was empty — they were busy attending a wedding, but they still managed to send a few words: “It’s because he has a hot temper,” “Poor family, greedy for wealth,” “You dare to be rude as soon as you walk in.” Only Mrs. Meera, who takes the bus nine stops a month, brings me a pot of vegetable curry or a bag of mangoes. She sits across from me through the glass, doesn’t ask “are you innocent,” doesn’t say “I believe you,” just gently reminds me: “Don’t skip meals. Don’t clench your teeth when you cry, it will damage your enamel.”

I didn’t know what to call that constant attention — love or redemption — until this morning.

The day Raj died, it rained from noon, and by evening it was as cold as ice in my lungs. I was washing the dishes when the phone rang. The neighborhood chief’s voice was urgent: “Come back quickly… Raj fell down the stairs…” When I ran back, the stairs were wet with soapy water stains, Raj was lying at the foot of the stairs, his left temple hit the edge of the step, blood soaked into the red cotton doormat. Mrs. Meera knelt beside me, her hands trembling, dialing the emergency number and using a towel to rub the blood like wiping a plate that had spilled food.

I still remember clearly the testimony the next day: “The couple had a conflict, argued, and fought”. The neighbors, who never said hello when I went to the market, suddenly remembered clearly: “Heard the sound of arguing”, “Heard the sound of broken furniture”. The owner of the pawn shop at the end of the alley confirmed that Raj was in debt for a large sum of money, and was being urgently asked for. A power of attorney for the sale of a motorbike in my name appeared on the investigation table. My name and signature were left alone under the red seal. I remember signing it one tired afternoon after work, Raj shoved a stack of papers into my hand and said “sign for me so I can get it notarized in time”, saying it was a “temporary loan”. I didn’t read it, just looked at my husband’s face.

The trial was as quick as a pot of boiling water covered with a lid. The autopsy recorded “a strong blow to the left temple, intracranial hematoma”. The lawyer hired by my husband’s family sat with his arms crossed. Mrs. Meera didn’t look at me — she looked at the slippers I was wearing at the time: old grey plastic slippers. I heard the hammer knock three times.

I went to the camp.

The first months, I lived like someone who had missed a breath: I always felt lost. In the evenings, I listened to the women in my room tell their stories: human trafficking, jealousy, fraud. Everyone had a “why”. I had no reason. Every month, Mrs. Meera came, put the bag on the tray, her eyes dark. I asked once, with the last bit of courage: “Do you believe me?” She didn’t answer. She poured water, and said… “Drink it. Lemon water. It helps you sleep.”

I was angry with her. Angry at the silence that was both trusting and skeptical, both sharp as a knife and cold as ice. But then the anger got tired. I started knitting — from the yarn she sent in: “Knit a scarf. It’s cold this season.”

It continued like that until my sentence was reduced for good behavior and I was released early. And she stood at the gate and said: “Go burn incense for him.”

We sat on the bus together, the windows were covered with rain. She held a cloth bag on her lap, her fingers trembling slightly like a long-unstrung guitar string. I looked sideways and saw a stray silver hair between her black eyebrows — a hair that I had always wanted to brush away but never dared.

The bus turned onto the path leading to the cemetery. The smell of damp grass wafted to my nose, like the smell of the camp laundry room when it rained. Raj’s grave was in the last row, its back facing the fields. The marble tombstone was cold, the inscriptions neat. The white chrysanthemums were tilted in the vase, someone must have just changed them. Mrs. Meera told me to wait, she bent down, and untied the rope that tied the tomb cover. I jumped in surprise:

“What are you doing, Mom?”

“Open it,” she said. “Let the scent and wind in.”

The tomb cover opened, making a soft groan like an old man turning over. I was stunned. There was no coffin. Where the wooden lid should have been, it was empty, with only a plastic envelope with a piece of paper pressed on it: “DNA test receipt – sample exchange – preservation 11/…/20…”

I knelt down, my knees touching the cold ground. The sound of the wind passing through the mango trees was like someone laughing dryly above.

Mrs. Meera squatted down, took off her shawl, spread it out on the edge of the tomb, and placed the plastic envelope on it. She spoke very softly, as if afraid of breaking something fragile:

“He’s not dead, my child.”

I looked up, not recognizing my own voice as I exclaimed, “Who… yet?”

“Raj. Mother… set it up. Mother was wrong. Mother is guilty.”

From the edge of that thin, dewy sari, the truth spilled out, unable to be contained.

Raj gambled. That whole year, he went in and out of the pawn shop like he was going to the market. I knew vaguely, but I believed “he was just playing a little bit.” That little bit turned out to be a mountain of debt. The night before he “fell down the stairs,” he received a phone call. His face was pale as if he had just swallowed ice water. I asked, he shouted — the rare time he shouted — for me to “not interfere” and then went to take a shower. To the stairs, slippery with soap suds.

Meera said: “They came to the house to search. I was afraid he would go to jail. I was afraid he would die on the street. I heard Mr. Sharma — the undertaker — say that the cemetery had a new, unknown body that looked similar. I… changed it. The forensic department… had an acquaintance. The mistake started with the first nod.”

I arranged a neat funeral. My cousin, a doctor, signed a paper. All the money was taken care of. I thought: “Hide him, let him go away for a few years, wait until things calm down and then come back.” But the police were investigating the “fall”. I needed a plausible story. People saw blood on the carpet, heard neighbors talk about the sounds of arguing. I… pushed the blame onto my son. A push. Clumsy. And cruel.

She paused. Her eyes looked into the empty grave as if looking into a deep well.

“I only thought about the immediate benefits,” she said. “The court was quick. I thought you were strong enough. I brought you food every month, as an atonement. I couldn’t sleep at night. I saw him come back, standing at the door, saying: ‘Mom, you pushed my wife down the cliff.’ I couldn’t take it anymore. So today I brought you here. I’m going to the police right now.”

I sat there, my hands gripping the concrete edge until it hurt. In front of me, a woman was holding a hoe, digging herself out of the hole she had filled, exposing herself to the wind. I had thought of so many curses to say to her during the dark nights in the prison. Now those words fell like dry leaves.

I gritted my teeth: “And… where is Raj now?”

She shook her head. “In the South. Hiding at the docks. I didn’t dare come. He sent me money once, telling me ‘don’t let her know’. I was… scared.”

I stood up and closed the grave. The sound of the lid hitting the cement was sharp and decisive. I looked at her: “Mom, go report it.”

She nodded, smoothed her hair, stood up, and dust fell from her knees like grains of salt.

We arrived at the police station at noon. Mrs. Meera wrote a petition. Confession. Body swapping, bribing the expert, setting up a fake crime scene, blaming her daughter-in-law. Each word she wrote was shaky, but steady. The officer on duty had eyes as round as an upside-down bowl. The old investigator of my case came, holding the petition with two fingers like holding a live fish. Taking a statement. Confrontation. Sealing the DNA piece of paper in a plastic envelope.

Late in the afternoon, the sky darkened, she put on her coat, turned to me:

“I was afraid you would die in the camp before knowing the truth. Now you know. I’m leaving.”

I didn’t cry. I didn’t scream. I just said: “Mom.”

I called her ‘mother’ — for the first time — before they locked the handcuffs around her wrists. She nodded gently, as if she had just received a cup of warm tea that was just right.

The corridor of the police station smelled of tobacco and sweat. The tree shadows at the top of the stairs. She walked. The sound of her leather sandals fell silent behind the iron door.

News of the empty grave spread faster than the smoke of straw. Relatives of her husband came in droves, some screaming, some shouting, some saying “she’s acting,” some cursing “an evil witch,” then suddenly fell silent when they saw the sealed record. Mr. Sharma — the man in charge of the funeral — was summoned. Later, I heard him say in the interrogation room: “She knelt before me. I… thought I was doing a good deed. It turned out I was creating bad karma.”

The case was reopened for a retrial. Police went to the South to find Raj. People said he was hiding in loading yards, changing his name and phone number like changing clothes. They almost caught him once, but he escaped through a tin roof. Finally, one rainy night, he was caught behind a warehouse.

On the day of the confrontation, I sat across from Raj behind the glass, my heart pounding like a runner who had no idea where the finish line was. He was thinner, his hair was long, his chin was covered in stubble. His eyes were downcast. His right hand, holding an imaginary cigarette, rubbed it against his knee.

“You…” he whispered, pointing at me. A tear flowed back inside. “You…” — he swallowed — “You are a coward.”

I didn’t say forgiveness. I didn’t say hatred. I didn’t ask why. I just asked: “Who was responsible for the wet stairs that day?”

“You.”

“Who told me to sign the papers to sell my motorbike?”

“You told me to sign. You lied.”

“Who ran to the pawn shop to ask for another week?”

“Your mother.”

I understood. Every story of sin starts with small words: wait a minute, a little bit, try, cover up. Cover up once, then twice. Then someone — Mrs. Meera — put her life on the table, staged a funeral.

The court overturned my sentence, suspended the case on the grounds that “there was no crime.” I didn’t feel happy. Just like someone drinking a glass of water after walking ten kilometers — the water flows down, without having time to taste it. Another case is opened — fraud in judicial activities, violation of a corpse, gambling — Ms. Meera is detained.

The day the order was read, she stood straight, not leaning against the wall. I looked at her, remembering the bags of autumn mangoes, the pot of curry she brought to the camp, the saying “don’t clench your teeth when crying.” I thought: Maybe she didn’t bring me food to make up for her mistake; she brought food because she didn’t know what else to do — it was the only way she knew to hold on to a string that was slipping from her hand.

I asked permission to visit her in the prison.

Her camp was different from mine three years ago. The walls were bright yellow, the smell of bleach was stronger. The iron door creaked. I sat in front of the glass, the phone receiver so old that the plastic was worn like leather. She walked in, wearing a blue-striped uniform, her hair still neat. Her eyes were sunken, but her gait was steady — like when she walked along the rice field when I first became a bride, her feet never sinking.

We looked at each other for a long time. She placed her hand on the wooden table, her fingers wrinkled like small streams of water. I placed mine on it, not touching, just measuring the distance.

“I…” I opened my mouth, my voice hoarse — the hoarseness of many nights in the camp, not daring to cry out loud. “I came to visit you.”

She started a little, like a fish in a basket twitching its tail. Her eyes were full of tears, but they did not fall. “Yes,” she said. “I’m fine here. I’m less scared. I don’t open the door to see him standing there any more nights. I can sleep now.”

I told her about how I got a job at a small garment factory, how Auntie Lakshmi hired me to sew by hand. About the debt I was gradually paying off. About my husband’s family, as silent as the yard after a rain. My sister, Priya, bought me an old phone, telling me to “practice taking pictures of flowers to relieve my boredom.” She listened, nodding, her mouth moving as if counting.

At the end of the session, I took out a ball of navy blue yarn from my pocket—the color of her favorite shawl—and a pair of knitting needles. “I’m knitting a scarf,” I smiled, “It should be done by the monsoon season.”

She didn’t smile. She leaned over, pressed her forehead to the glass, and exhaled a faint trail of steam. “Don’t skip meals,” she said as she used to. “Don’t clench your teeth when you cry.”

“Yes, Mom,” I replied. I called out the word “Mom” clearly, my throat free of any obstruction. She closed her eyes and took a deep breath—the breath of someone who had just put down a heavy sack of rice she had carried for ten years.

We sat like that until visiting hours were over. When we left, a light rain was falling. The farmyard smelled of freshly cut grass. I passed through the gate, looked up at the iron sign “Good Reform – Good Life”, and felt a howling wind in my heart.

A while later, the newspaper published the verdict: Mrs. Meera seven years in prison for violating a corpse, falsifying records, bribing public officials. Raj two years in prison for gambling, plus eighteen months for evasion, suspended. Mr. Sharma three years in prison. His doctor cousin had his medical license revoked.

The neighbor who used to sprinkle chili powder in front of my house to “exorcise evil spirits” suddenly changed his tone. They came over, put a plate of puri on my table, and said while eating: “Everyone makes mistakes.” I smiled politely. The past has a way of turning those who say cruel words into old storytellers, as if they were just spectators.

One afternoon, I stood in front of my house, watching the sunlight shine down the alley. The sound of the garbage truck outside the alley stretched out like a piercing metallic melody. Raj came. He stood in the distance, his hands clasped together. I waited for an apology. He said nothing. He bowed his head deeply. Then he walked away.

I didn’t call him back. We had already spent as much time together as we could. The rest — for me — were visits to my mother.

Once a month, I went to the camp. She started writing letters. Thin sheets of paper, slanted letters: “On… month… today is sunny. Geeta has a toothache in the room. Mom will share some yogurt with her.” and “Tomorrow, when we go to visit our great-grandfather’s grave, bring me white chrysanthemums.”

Once, she wrote: “I kept thinking: why didn’t I take you by the hand and leave that day? I was afraid of my family, afraid of the village, afraid of people gossiping. I named that fear ‘keeping my honor’. The name sounded so good, so I nurtured it. It was bigger than you.”

I read it, folded it, and put it in a cardboard box. Each letter was a brick paving the path to my house — a path that had been blocked with mud.

At Tet, the camp allowed family members to send gifts. I brought the scarf I had knitted. Navy blue. She put it around her neck, stroking the edge of the scarf like a child’s hair. She smiled very lightly. That smile no longer had the tense pride of the past — only wrinkles radiating from the corners of her eyes, warm like a sudden ray of sunlight on the carpet.

Before I left, she told me: “When I leave, I want to go back to that grave. Not the grave. That place. Put a white chrysanthemum for your sister-in-law. I owe her a stick of incense.”

“Yes, Mom,” I replied.

One afternoon in March, the white chrysanthemums were in full bloom at the market. I took two bunches and went to the cemetery alone. The wind blew the red cloth that people had dried on the edge of the field, fluttering like waves.

When I got there, I opened the grave again. The bottom was still empty. I dropped in a small piece of paper: “Mom, I came to visit. I’m calling you. Can you hear me?” Close the lid. Put a chrysanthemum. Take a step back. Fold your hands.

The sky did not respond. But a sparrow perched on the tombstone, tilted its head to look at me, and chirped very softly. I smiled. A knot that had been there for years suddenly unraveled like a thread.

If someone had asked me, “Where does this story end?”, I would have said: it didn’t end in the empty grave, it didn’t end in the DNA, it didn’t end in the handcuffs. It ended in the visiting room, when I said, “Mom,” for the first time in ten years, and she nodded with the nod of someone who no longer needed to keep herself in order.

And I—the daughter-in-law who had been sentenced, who had been scorned by relatives with cruel words—had relearned to stand firm in the daylight. Not hiding from anyone’s shadow. Not demanding a verdict for anyone. Just renaming each event: that was a mistake, this was pain, that was redemption, and today was visiting my mother.

I folded the handkerchief neatly, wrapped it in last month’s newspaper, and put it in the basket. Tomorrow, I would take the nine-stop bus again. Tomorrow, through the glass, she will ask: “Have you had breakfast yet?” I will answer: “Yes, Mom.”

And I believe — simply believe — that every time we call each other like that, the past ten years recede a little further, giving way to a new patch of day, blue, like the color of the woolen scarf around her neck

News

The husband left the divorce papers on the table and, with a triumphant smile, dragged his suitcase containing four million pesos toward his mistress’s house… The wife didn’t say a word. But exactly one week later, she made a phone call that shook his world. He came running back… too late./hi

The scraping of the suitcase wheels against the antique tile floor echoed throughout the house, as jarring as Ricardo’s smile…

I’m 65 years old. I got divorced 5 years ago. My ex-husband left me a bank card with 3,000 pesos. I never touched it. Five years later, when I went to withdraw the money… I froze./hi

I am 65 years old. And after 37 years of marriage, I was abandoned by the man with whom I…

Upon entering a mansion to deliver a package, the delivery man froze upon seeing a portrait identical to that of his wife—a terrifying secret is revealed…/hi

Javier never imagined he would one day cross the gate of a mansion like that. The black iron gate was…

Stepmother Abandons Child on the Street—Until a Billionaire Comes and Changes Everything/hi

The dust swirling from the rapid acceleration of the old, rusty car was like a dirty blanket enveloping Mia’s…

Millionaire’s Son Sees His Mother Begging for Food — Secret That Shocks Everyone/hi

The sleek black sedan quietly entered the familiar street in Cavite. The hum of its expensive engine was a faint…

The elderly mother was forced by her three children to be cared for. Eventually, she passed away. When the will was opened, everyone was struck with regret and a sense of shame./hi

In a small town on the outskirts of Jaipur, lived an elderly widow named Mrs. Kamla Devi, whom the neighbors…

End of content

No more pages to load